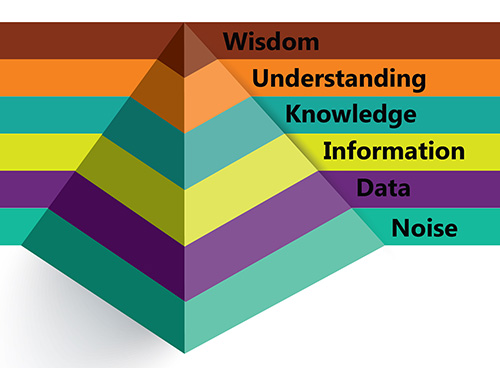

A picture is worth a thousands words, they say. Take a look at this graphic: it almost doesn’t need any comment.

It makes the point that wisdom floats on top of understanding and understanding is built on knowledge.

It also clearly separates information and data. It’s been a saying of mine for decades that information implies consciousness. Information doesn’t mean anything much unless there is awareness present.

Shorn of interpretation and meaning, information is just data. A ton of data points mean little or nothing, unless there is intelligence viewing it, which can spot the patterns.

Below that is just noise.

It may be more important to understand noise than to understand wisdom (in a way). Noise appears random, arbitrary, unimportant, is not aligned and therefore not useful. It’s the opposite of coherence. Noise is a sort of psychic turbulence. It is best avoided.

Unfortunately, our lives are overflowing with noise: television, unnecessary phone calls, email spam, FaceBook, Twitter, billboards, piped background music, leaflets, slogans and flashy images.

Attention Units

In a now-famous paper in 1956, George A. Miller (then at Harvard, now at Princeton) suggested that the capacity of the human mind when active is limited to roughly seven attention units, though occasionally this can go up to nine.

The mind has to filter out which seven, from billions of units of input noise. How does it do it? You might well ask!

Bear in mind that the seven “units” applies only under optimal conditions. You will see at once that someone in a heavy case reload will have four, five or six of these units snapped up, reducing working-memory, and meaning that people cannot possibly learn who are sick, upset, frightened or greatly fatigued.

What Miller called the informational bottleneck has since been recognized as a profound constraint on human cognition. One solution Miller came up with is “chunking”: reducing the size of each bite or unit of attention. As Miller put it, “A man just beginning to learn radiotelegraphic code hears each dit and dash as a separate chunk. Soon he is able to organize these sounds into letters, and then he can deal with the letters as chunks. Then the letters organize themselves as words, which are still larger chunks, and he begins to hear whole phrases.”

That sort of process is obviously central to most kinds of learning.

The other attractive solution is to control attention, so that unwanted stimuli do not crowd the working memory. That might sound simple. But it’s not a given; maybe poor attention control lowers task performance or maybe being engaged in a task stimulates and tunes up the ability to concentrate and increases working memory capacity?

Supervisors and educators should read the book The Overflowing Brain: Information Overload and the Limits of Working Memory by the Swedish neuroscientist Torkel Klingberg (Oxford University Press) for more on this.

I’ll follow up in the near future with a piece about multi-tasking, in other words using more than one attention unit at a time. Does it work?

For me it’s difficult to tell noise from information. It’s more an art than science.

How to know in what we must focus? Sometimes there is info relevant to us that we just dismiss and sometimes we pay attention to garbage.

That’s a special technique in Supernoetics we call “data evaluation” Mori. How to tell what’s useful knowledge. You can catch a video I did here, on YouTube:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B-X9TGPrtHo&spfreload=10

Enjoy! Keith

Very gracious offer

Ingenious idea

A live’s WISDOM

Thank you

Ed

Thx Dr Keith.. a beacon at least!